Zeitgeist

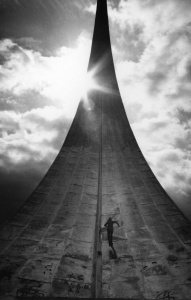

The exhibition title ‘Zeitgeist’ is a philosophical term, which literally translates as ‘spirit of the time’ and is the most accurate way to describe the artistic career of Sergei Borisov — one of the most sought-after Russian photographers at the turn of the century. By introducing this term in relation to Borisov’s work we strive to communicate the variety of the author’s artistic language. He never was a documentary photographer and always embraced a variety of genres: portrait, nude, studio and cityscape photography. Borisov is frequently dubbed ‘the chronicler of Moscow and St. Petersburg’s underground scenes’ and ‘the glorifier of Moscow and its bohemian community’. Although being mostly staged, Borisov’s photographs are suggestive and metaphorical representing a variety of attitudes and emotional conditions: from poetic and sublime states to ironic expressions and grotesque scenes. It is always the individual — the ‘new individual’, the ‘hero of the time’ — that is of core interest to Borisov. Photography as a medium can be thought of as a leveler of different currents in both life and culture. That is why what the photographer sees through his camera lens is the difference between reality and the author’s inner world — this difference allows the artist to take an ironical stance. Borisov has always been acutely sensitive to processes in Russian society: be it the collapse of the USSR (‘The Russians Are Coming’, 1985), the emergence of the new Pepsi generation (‘Solitude’, 1993) or the rise of selfie culture (‘Selfie with Putin’, 2014). Rather than merely document reality, Borisov is drawn to symbiotic relationships between the subject and its surroundings. The artist’s astonishing capability to come up with succinct titles for his works allows him to impart additional meanings to them. In ‘Catwalk’ (1987) and ‘Glasnost and Perestroika’ (1986) the self-contained image enriched with semantic connotation acquires a new depth. Sergei Borisov’s visual language is marked by the use of landscape — mostly the architecture and panoramas of Moscow — for conveying the emotional states of his heroes and creating multilayered allusions. The interrelations between architectural elements, elaborated compositions, and the playful use of perspective and light on the one hand, and personages on the other, have the effect of a thrilling sensuousness. It is notable that the sky constitutes an important part of Borisov’s allusive framework often serving to convey metaphorical meaning. In the works such as ‘Confession’ (1993) and ‘Masha on the Chimney’ (2003) the breathtaking views allow one to infer the inner state of the personages that literally rise above their drama. An interest in the nude figure as the embodiment of beauty is an integral part of Borisov’s visual language. The body in his work is not an object of desire — devoid of sex appeal it nevertheless evokes a certain aesthetic sensation. The expressive power of Borisov’s works largely relies on combining natural and at the same time sublime poses with emblematic attributes of particular epochs. The nude figure portrayed in Borisov’s early works made him the pioneer of this genre among Russian photographers and to a large extent acted as a powerful symbol of opposition to Soviet ideology. The provocative photographic series of women with symbols of the USSR (‘Schoolgirls’, 1989), (‘Display the Initiative!’, 1987), revolutionary for their time, address the Soviet reality of tabooed themes. In Borisov’s later works the nude figure came to symbolize the freedom of the perestroika epoch and in his recent pieces it serves as a means to convey a radical gesture expressed by the model. Particularly noteworthy is the legendary ‘Studio 50A’, established by Borisov and serving him as a studio from the early 1980s to the present day. From the late 1980s to the early 2000s the studio was the powerhouse of Moscow cultural life: diplomats and eccentric artists, underground musicians and freaks, celebrities and collectors — to a varying degree all of these figures were a part of the studio. A circle of freethinking creatively empowered people formed around Borisov and his ‘Studio 50A’. It was there he took most of his photographs. Borisov’s genius for creating ‘icons’ of the time makes him one of the most sought-after photographers in Russia. Just like ‘Sunset’ of 1985 and ‘Acrobat’ of 1993, ‘Pas De Deux’ of 2016 can undoubtedly be regarded as a symbol of its epoch. ‘Zeitgeist’ is not a retrospective in the strict sense of the word due to the continuity of Sergei Borisov’s creative process — staying responsive to contemporaneity he maintains his relentless commitment to record it. Catherine Borissoff