Escape!

Gardens and parks, whether they flourish in inhabited landscapes or internally, in our souls, are well-kept niches of great free nature cultivated in private spaces. A garden is a miniature replica of wider nature, and we can all pass judgement on the universe without leaving the confines of our own small plot. This garden can reflect the essence of its owner like a mirror. The palette of human emotions is revealed in the elements and outlines of the garden, obliging you to plunge psychologically and emotionally into the primordial Garden of Eden – a natural source of creative inspiration, relaxation and soul-healing. The garden is a primeval ideal, the model of a problem-free world, a symbol of security and tranquillity, an ideal image of exquisite diversity and conceptual integrity.

Enjoyment of the natural world and sensory cognition of this has permeated the history of world art since antiquity. In the 18th to 19th centuries the natural environment became a source of inspiration for philosophers and theorists, before serving as the basis of a rebellious, romantic culture. Already, at the beginning of the 20th century, the garden becomes a utopian model of the perfect city. A little later, in the 1960s, it was Flower Power that became a symbol of the resistance and non-violent protest that shaped the birth of American and then world counterculture.

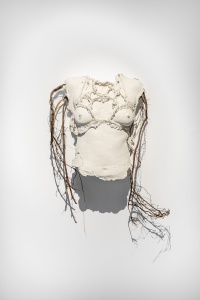

A separate subject in this context is the allegorical and symbolic group of visual images associated with flower beds and rose gardens, which in the 20th century, from the advent of surrealism, was used to perceive, interpret and explain female sensuality. Later contemporary artists increasingly transformed this tendency into a critical view of objectification of the female body. Bound either by game-playing fetters or ropes of torture, the female torso of Mayana Nasybullova sprouts roots, as if reborn over and over again from the ashes of suffering. Lena Artemenko’s ‘sprouts’ refer to problems in the relationship of the female with herself and the world outside as she gains self-identification – will they flourish or perish without a careful approach? In Irina Petrakova’s work the unisex camouflage of coarse sweatpants flowers as an orchid of saving femininity, capable of balancing the raging Yang and turning aggression into a creative channel.

Today the issue of gardens may be increasingly oriented towards ecological thinking, to problems of the post-human or biotechnological experiments fuelled by doubts about the guaranteed global well-being of the planet. Sergei Borisov’s overgrown ‘Grandma’s Garden’, overhung by ponderous ghosts of the past, thirsts for revival and renewal, corresponding to the development of progressive modernity. Such modernity, where grass is not painted green, cannot replace the concept where green leaves grow on birch trees instead of those frozen in the tree bark, as seen in Damir Muratov’s ‘Birch’.

Most importantly, man still carries the memory, the imprint of a lost Eden such as that glimpsed by Lyonya Purygin, a creation worthy of its Creator; we continue to try and restore what was lost, recreating luxury and security in proportion to our talents and material capabilities for ourselves and our environment.